When studying history, it’s politics that always comes up first. We analyze events by looking at the people involved. What did they do as a group? What were they thinking? Was there a key figure who set everything in motion? It always comes back to this meticulous unpacking of the event. But once you start studying the history of art, a new player emerges.

Art and politics are like two closely linked chemical elements. One is uranium – immensely powerful – and the other is thorium, similar in nature but slower and non-explosive. In our minds, they’re fused as fundamental parts of social life. When times are good, they function as a unified force (glory). And when everything is really bad, they still act as one (propaganda). Sometimes, though, they become sworn enemies, trying to defeat one another – only on vastly different time scales. Their relationship defies fixed categories or clear patterns. It’s unpredictable. It’s complex. It’s alive.

This story begins at the dawn of humanity, when the world was still hot before it turned cold – and now is hot again. As trade and social dynamics within small groups brought Politics 101 to light, art emerged on the walls of caves in France. Fast forward to the famous debate between Aristotle and Plato: is art dangerous because it distorts reality and affects people? Or is it useful for exactly the same reasons? Fast forward again to Hegel: is art now too weak to affect anything? Spoiler from the future – Karl Marx: not only art is not weak, it is actually essential to politics. The full circle is completed. Art doesn’t simply affect the working class; it is also a tool for education. It shapes the person who acts politically.

Siegfried Kracauer goes further. For him, art is political on an irrational level. Society finds its reflection in every artistic representation of reality, even the most popular ones. He examined pre-WW1 German films and identified early symptoms that would eventually lead the German bourgeoisie to vote for Hitler in 1933. His famous idea – that Hollywood gives people what they want before they even know they want it – works both ways. Is it the studio that decides what to produce, or is it actually society’s tendencies that dictate the studio’s direction?

Moving closer to our times, let’s look at censorship. Essentially, there are three critical moments in a film’s life when censorship can interfere:

- Before it even starts – Here, we’re left with nothing to examine because nothing has ever been born.

- During production – Depending on the circumstances, the artwork mutates under political pressure and becomes more or less metamorphosed.

- After completion – This affects works created long before the current political moment (again, the question of time scale). It usually takes the form of prohibition or altered interpretation. Due to the slow-moving nature of art, these works are rarely re-evaluated or revised. Besides, evil lacks talent – as is well known.

Let’s examine three examples of prohibited films and see how modern-day censorship works in the Russian state.

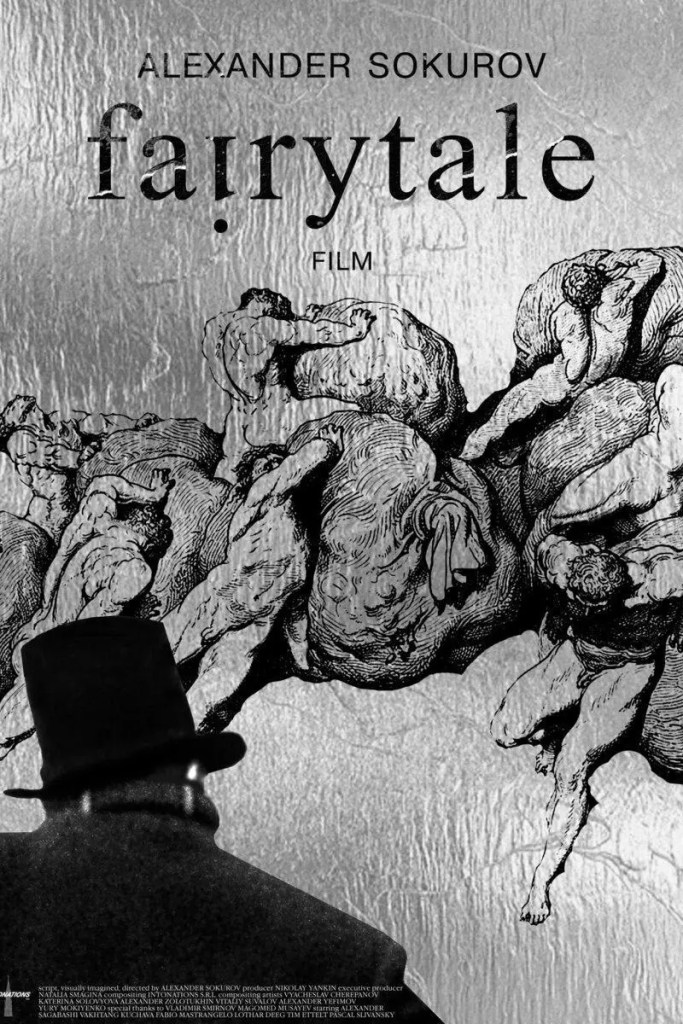

- Fairytale (2022) by Alexander Sokurov

This film was never released or distributed in Russian cinemas. Created without support from the Cinema Fund, it was entirely made from archival materials, without actors. The film was banned – refused a distribution license without explanation. The only reference was to subparagraph “ж” of paragraph 18 in the rules on release certificates: “in other cases determined by federal laws.” And just like that – imagine what a director lives off of – three years have passed, and no new films have come from one of the most important Russian intellectuals of the 21st century.

- Mr. Nobody Against Putin (2025) by Pavel Talankin

A documentary shot by a schoolteacher from the town of Karabash, Russia. The footage was smuggled out of the country for editing. Highly rated at Sundance 2025, the film forced the director into exile in Prague.

- Beanpole (2019) by Kantemir Balagov

Though his last film dates back to 2019, Balagov remains a key figure when speaking of contemporary Russian cinema. After leaving the country in 2022, he began preparing his English-language debut abroad. His absence speaks volumes. Like many others, he didn’t face a direct ban — but the air became unbreathable. His story reflects a quieter form of censorship: the kind that pushes voices out, suffocates them gently, and leaves the screen silent long after the artist has left.

Smolkin Viktor

Fonts:

https://themercury.com/news/national/russias-mr-nobody-gambles-all-with-film-on-kremlin-propaganda/article_72f57606-5bcf-5399-b35c-e0209b386399.html

From Caligari to Hitler by Siegfried Kracauer 1947