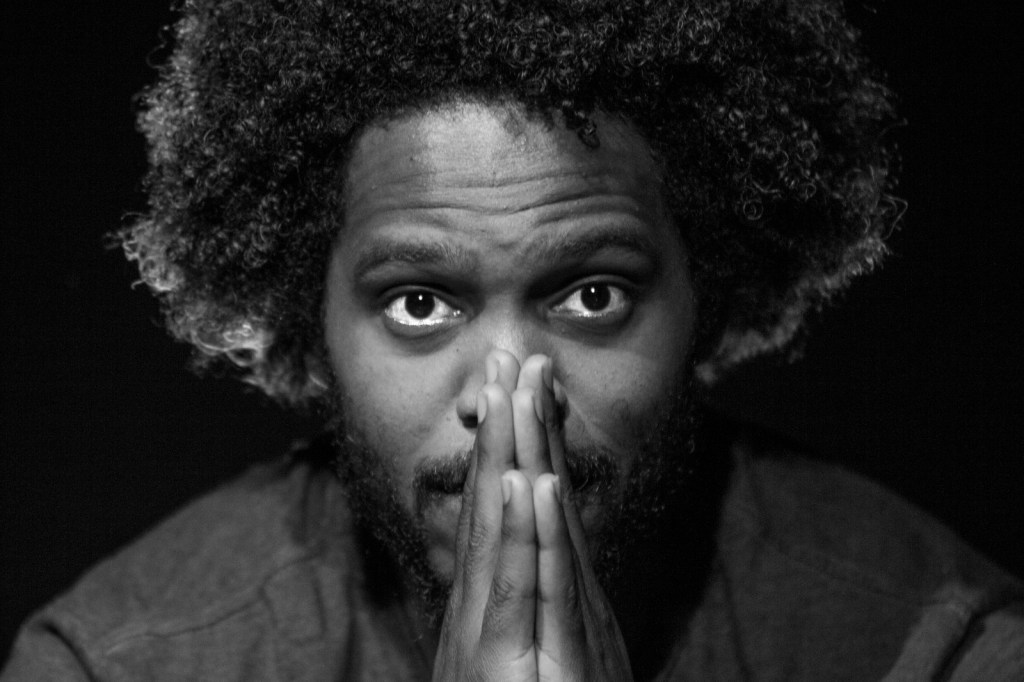

An interview with Jared McNeill

Jared McNeill is an incredible actor and director. Supported by continuous research, his work explores the infinite possibilities of performing and bringing people together. In the first part of this interview, we’ll discover more about his idea of theater, his studies, and his collaboration with Peter Brook.

Special thanks to Jared McNeill for the time he dedicated to us.

If a child asked you: “What is theatre?”, what would you answer?

It’s a bedtime story. We tend to overcomplicate things when we talk about theatre, but when you’re reading a bedtime story, something natural happens. In The Three Little Pigs, you instinctively use a deep, dark voice when the Big Bad Wolf tries to come through the door. Everybody does this, not only actors, because we tend to experience storytelling as a space where we allow our imagination to show us different possibilities. And storytelling isn’t so far from the beginning of the history of theatre. For example, ancient Greek theatre was based upon the stories of people who set off on ships and went to fight wars. Those stories later became mythologies, but they had started as news. Similarly, the African griots travelled from East to West through the desert carrying stories with them.

Anytime a story gets carried forward, it has a universal value. It’s very democratic because a bad story will disappear, or people won’t listen. On the contrary, a good story can engage people on two different levels, personal and universal. They’re like two roads moving in opposite directions inside yourself: the personal moves towards the universal and vice versa. Essentially, when you’re listening to a good story — or when you’re telling one — you’re finding a space within yourself for these universal values, but you’re also attaching your uniqueness to them. To visualise the power of stories, I always think about two images that everyone is familiar with. Sitting on the beach and watching the waves or laying down in a field and looking up at the stars: those are experiences that you can share with your friends, but they are also deeply personal. I believe that good stories serve the purpose of connecting us personally to the universal, like drawing a string.

You’re both a director and an actor. Do these roles allow you to have a wider perspective?

During my career, acting and directing have continuously influenced each other. I studied theatre and visual arts, and I was in Peter Brook’s company for ten years. Later I transitioned into directing, first working as Peter Brook’s assistant director and then starting to tell my own stories. It really comes from within, from the need to tell stories in a certain way. It has nothing to do with the ambition of being better than other directors.

I also have great respect for actors, which is somewhat lost today. This is something I took from my maestro, Peter, who almost treated them as if they could be shamanic. I always have too many ideas and I’m not good at just picking one and telling the actors what to do, I prefer when there is an exchange. That’s very different from a lot of directors, who expect the actors to fit into their idea. I’m not able to do that and it used to be a problem, because I tried to force myself. Now everything I make reflects where I was when I was making it and who I was making it with.

Imagine you have eight people in a room: I could create something that moves only me, or something that allows itself to be transformed by crossing arms with others. At the end of the day, that creation could move at least eight people and that doesn’t happen if you simply impose your own vision. Something can be beautiful even if it comes from my head and I give the actors strict directions, but that’s not the point. The point is that, when everyone is mobilized and has collected around a deeper question, there’s another energy added to the performance. I’ve always found that it’s more powerful.

You studied at Fordham University at Lincoln Center in New York, then you moved to Europe and now you’re in Italy. How has this journey impacted your art?

It had a huge impact. Studying in New York was a great experience, because I didn’t grow up there. Seeing the commercial side of the industry was eye-opening. It is a very ambitious city, it asks a lot, and it feels like no other place exists. I’m happy that I experienced that “hustle”, like they say over there. It’s a place where the acting community is very tight-knit. You can see someone at a Broadway show and then go to a small downtown theatre and meet that person at a reading. You could be a new actor and still find your way into rooms with the big names. I haven’t found those things in other places. They say if you make it there, you can make it anywhere, so why would you go look elsewhere? When I left to go to Europe, people were telling me it was a bad idea, but the benefit of traveling was to discover new possibilities. When I graduated in New York, I thought of acting as a business. Going into other cultures allowed me to see different ways of doing theatre.

Then I worked with Peter Brook. I always say that what he showed me isn’t magic, because it’s not hippy-dippy stuff, but it’s magical, because it was giving concreteness to the invisible. He was interested in the real cultures that explore the invisible with rites and rituals. Peter didn’t invent those things, but he brought them into Western consciousness through theatre. He did a great service in bringing a multicultural aspect to his work. The first performance I worked on with him was with people from Palestine, Israel, Japan, Poland, Mali, Nigeria, Spain, all in the same room. We shared stories, traditions, music. We could perform in magnificent theatres, like the Sydney Opera House, and do workshops in the suburbs, for example with Aboriginals on the outskirts of Sydney. The fortune in that duality was being able to draw the line between the two and to see the value in both.

Travelling also teaches you to be open and receptive. When I’m on tour, on the first day I walk around and get lost. It’s useful to get a sense of the locals’ rhythm and how they talk to each other. It’s important to know who I’m performing for.

You were Peter Brooks’ assistant director, what was it like?

I worked with him and his collaborator, Marie Helene Estienne. At the beginning, I found my role in assisting simply because everything else I did was wrong! I was the last person to be taken in the group, so everybody was already comfortable. I was throwing myself into a new situation, but it was so different from anything I’d experienced that it took time to understand. I just tried and failed many times. This is not a joke: every time I stepped foot on the stage, they would cut the scene, or every time I opened my mouth to say something, they’d cut the text. One day Peter told me they were doing a version of the show that I wasn’t in. So, I just sat and watched. There was an actor who didn’t speak any English, and I was asked to help him with the text. In the show there were a few other people who did not speak English fluently, so I started helping them as well. Peter and Marie Helene would change things frequently, and it was very easy for me to remember what the changes were, so I started having a voice. Between that and helping the actors with their English, I found a useful role. That’s how I became an assistant to the director. I would help with rehearsals, auditions, and workshops. It grew to the point where they would send the shows on tour, and they wouldn’t even come; I was the one bringing them into the theatres.

Anna Baracco