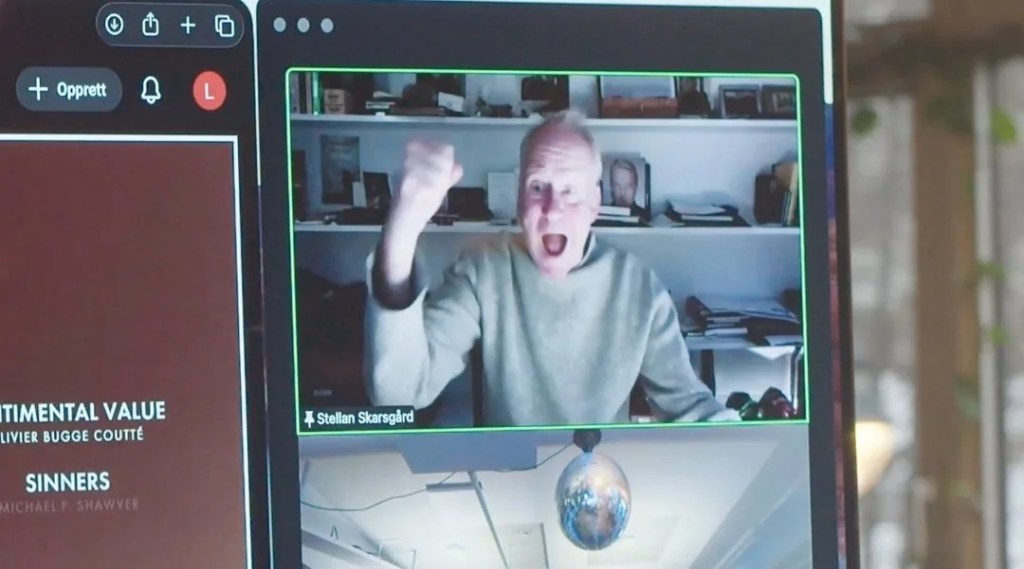

Oscar silly season is coming along this time of year. With 9 nominations, one of the leaders is Sentimental Value by Joachim Trier. The latest hit in European cinemas is a great example of European collaboration and how, by working together with the Northern countries, we might put up a fight against American cinema. However, in discussing the film itself, it is necessary to be as honest as possible; to understand the artistic flaws is to get closer to a better understanding of how to make cinema that relates better and more closely to the people of Europe.

Let’s, however, move on to a more specific analysis of the film. If the confusion in the last film by Trier, The Worst Person in the World, could be masked under the claim of being a ‘crisis’ representation, in his latest work, Sentimental Value, the explanation does not hold: representing an artistic or world crisis cannot always just mean chaos. The viewer, together with the poor actors, is left in a void of sense created by the director. The scope of psychological drama — as this film, however comedic, falls under the dramatic genre — is to provoke a response in viewers, to let them imagine and understand. Such a drama may lack the connection force of comedy, but it makes up for it on the semantic level with themes, values and heavy lifting. This film lacks everything, and to demonstrate this, let’s compare it to Blue Moon by Richard Linklater.

Comparison study: Blue Moon by Richard Linklater

Both films contain a personal drama together with an artistic drama. An old man with a past of glory tries to reconnect with a significant other using the only language known to him: art. This is a description for both films. One may argue that the focus in Sentimental Value is shifted much more towards the family relationship dynamics. On the contrary, it feels like Hart (portrayed by Ethan Hawke) is subtly always focused on his loneliness. In every scene, sooner or later, the topic of his relationships arises, yet it is so tightly bound to his artistic side, so well-written into his life story, that one cannot help but think: are art and life somehow intertwined? Is one a problem for the other, and viceversa? Being a comedy, it ends — better yet, it starts — with a total vision of reality: he is dead, he died soon after, he already was dead. The film feels hopeless, but not completely. There is some light at the end of the tunnel, even though the tunnel means death.

Trier’s film lacks all that and ends up on an unexpected reunification note. Cinema is powerful, but Trier forgot to explain to us why, as he was too busy constructing the flashbacks of a long-gone past and weird love geometries around Nora (Renate Reinsve). The dramatic structure around the house feels abrupt, as if something too dramatic was inserted into what is more of a melodramatic film. Many reviews highlight the resemblance of the film to Bergmanesque dramas inside closely related spaces. However, in comparison, for example, to Fassbinder’s Veronika Voss and the space of the apartment, full of allegories and metaphors on modern Germany and so well-written within the cinematic narrative structure, it shows a certain weakness.

The film feels too kind, too polite, too clear and — from a more formal point of view — too boring. Somehow, all the dialogues are shot on a handheld camera that neither makes us closer to the characters nor gives us freedom, because it all happens inside and with thousands of editing cuts alongside. Where Linklater shows a careful use of space and movement inside the frame, Trier’s characters live in a cinema set, literally, where nothing feels honest or connected.

The film conveys emotions beautifully and, together with excellent actors, it really aspires to tell the story in cinematic language. The characters are not just well-played — to which the 4 Oscar nominations for acting allude — but they are well-constructed as well. The characters are very close to us, the viewers; they are really confused about what is going on. There is plenty of room for their thoughts and sidelines, with them resting alone, going on a trip with colleagues, or simply spending time. Their life arc does not evoke questions — it is what Trier does best — but the world around them, the places and the narrative structures suffocate and distract them. There is simply no time for all of that in an already long, 130-minute film. Might it have been a great deal as a miniseries?

The film drowns in its own past; chaotic and misunderstood, it stays at the border between art and life. In a modern world full of unprecedented events, the film tries to convince us that life is understandable and could be solved as an equation. That is what makes it phony: its unrealistic promises.

Smolkin Viktor